“I grew up in a very humble home, there were a dozen of us in a small room,” remembers chemist Omar Yaghi.

They had to share that space even more: in one half “we slept, we ate” and, in the other half, there were some cows that they raised.

Yaghi’s parents were Palestinians and, after being forced to abandon their land, they arrived in neighboring Jordan, where he would be born in 1965.

Given the lack of basic services in the area where they lived, one of the tasks that his parents gave him as a child was to find water.

The supply was made available to families in the area every two weeks for a few hours.

“We stored as much water as we could in those four hours, that was the water we would use for two weeks. If it ran out, we had to look for another source,” the scientist said in a video of the Tang Prize, which he won in 2024.

His childhood memories were vividly recalled on Wednesday, October 8, when he received the news that he had won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

“I was born into a family of refugees,” he told a journalist on the award’s website.

“I think my father finished sixth grade and my mother couldn’t read or write.”

This is the story of the extraordinary journey of someone who is considered the father of the field of metal-organic structures.

The drawings that bewitched him

And for Yaghi, his life “has been quite a journey,” one that science allowed him to take.

“Science is the greatest equalizing force in the world,” he noted.

The professor at the University of California at Berkeley shared the Nobel Prize with Susumu Kitagawa and Richard Robson.

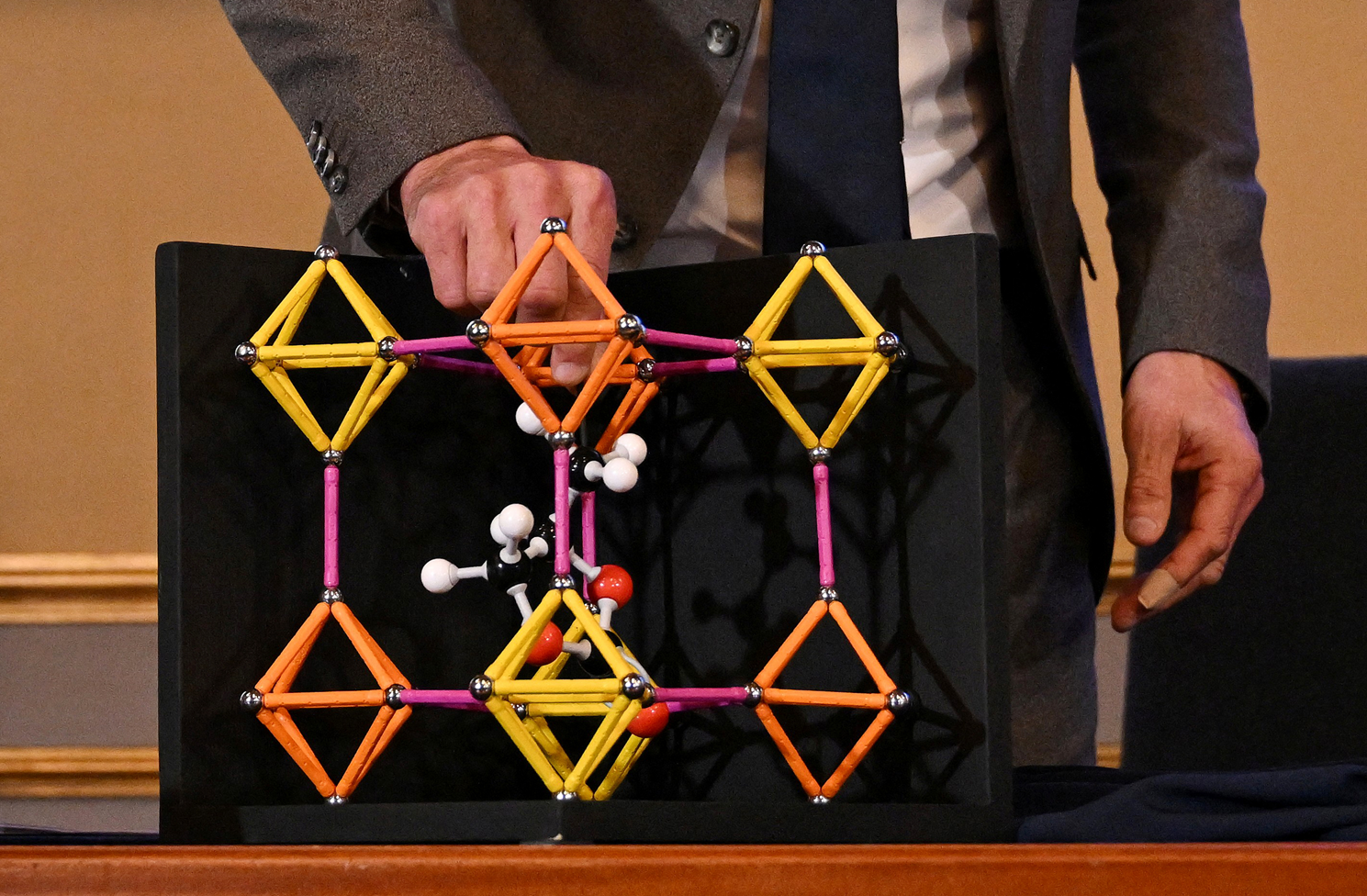

The Swedish Academy of Sciences highlighted in the work of the three the feat of developing a “new molecular architecture.”

And in Yaghi’s case that development began with something he saw when he was 10 years old.

After managing to enter a library, he approached one of the shelves and grabbed a book at random.

The drawings of some molecules left him absolutely captivated, he said in the Tang Prize video.

And although he didn’t know what those illustrations were about, that moment became a kind of treasure that he wanted to keep secret.

He remembers that he was a quiet, independent child who loved to read and study.

At the same time that he was wondering “what things are made of,” he helped his father in a store he owned.

In a talk he gave to young people at Hsinchu Senior High School in Taiwan, he said that helping his father was absolutely crucial in making him “appreciate quality and hard work.”

Cleaning the tables, the windows, making the store look attractive to customers, he learned the work ethic.

“He taught me that if you’re going to do a job, you have to do it right. Otherwise, don’t do it. He taught me that every day.”

“An incredible commitment”

His father, who owned a butcher shop in Amman, the Jordanian capital, envisioned a different destiny for Yaghi and told him he wanted him to go to the United States to continue his education.

But he, at 15 years old, wanted to stay with his family, attend university and work in Jordan.

His father insisted and convinced him.

“I am very moved to see how my refugee parents dedicated every minute of their time to their children and their education, who saw it as a way to get ahead, to overcome difficult situations. That requires an incredible commitment,” said the scientist in a press conference after learning the news of the Nobel Prize.

“And I didn’t lack love. We didn’t have many of the comforts that others had, but I did have a lot of love.”

He traveled and enrolled in a community school in New York.

“As a teenager, he made his own way in the United States,” Jorge Andrés Rodríguez Navarro, professor at the Department of Inorganic Chemistry at the University of Granada, tells BBC Mundo, who maintains not only a professional but also a friendship with the chemist.

Young Yaghi supported himself with the money he earned bagging groceries and cleaning floors, while he excelled academically. He graduated as a chemist with honors.

The education he received was reminiscent of him after learning that he had won the Nobel Prize.

“This recognition is really a testament to the power of the public school system in America, which takes people like me, who come from very disadvantaged backgrounds, from a refugee background, and allows you to work hard and distinguish yourself,” he said.

“A great inspiration”

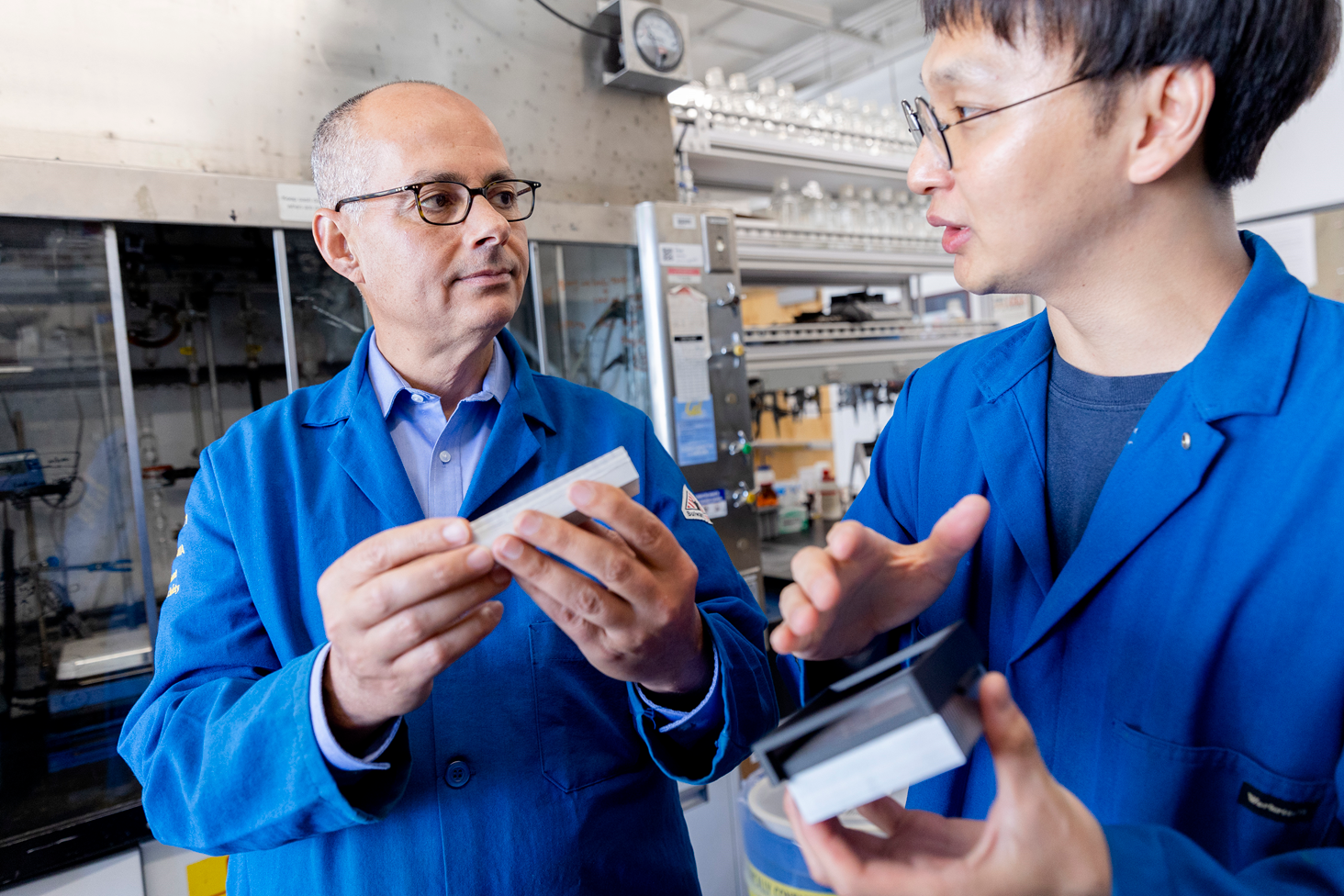

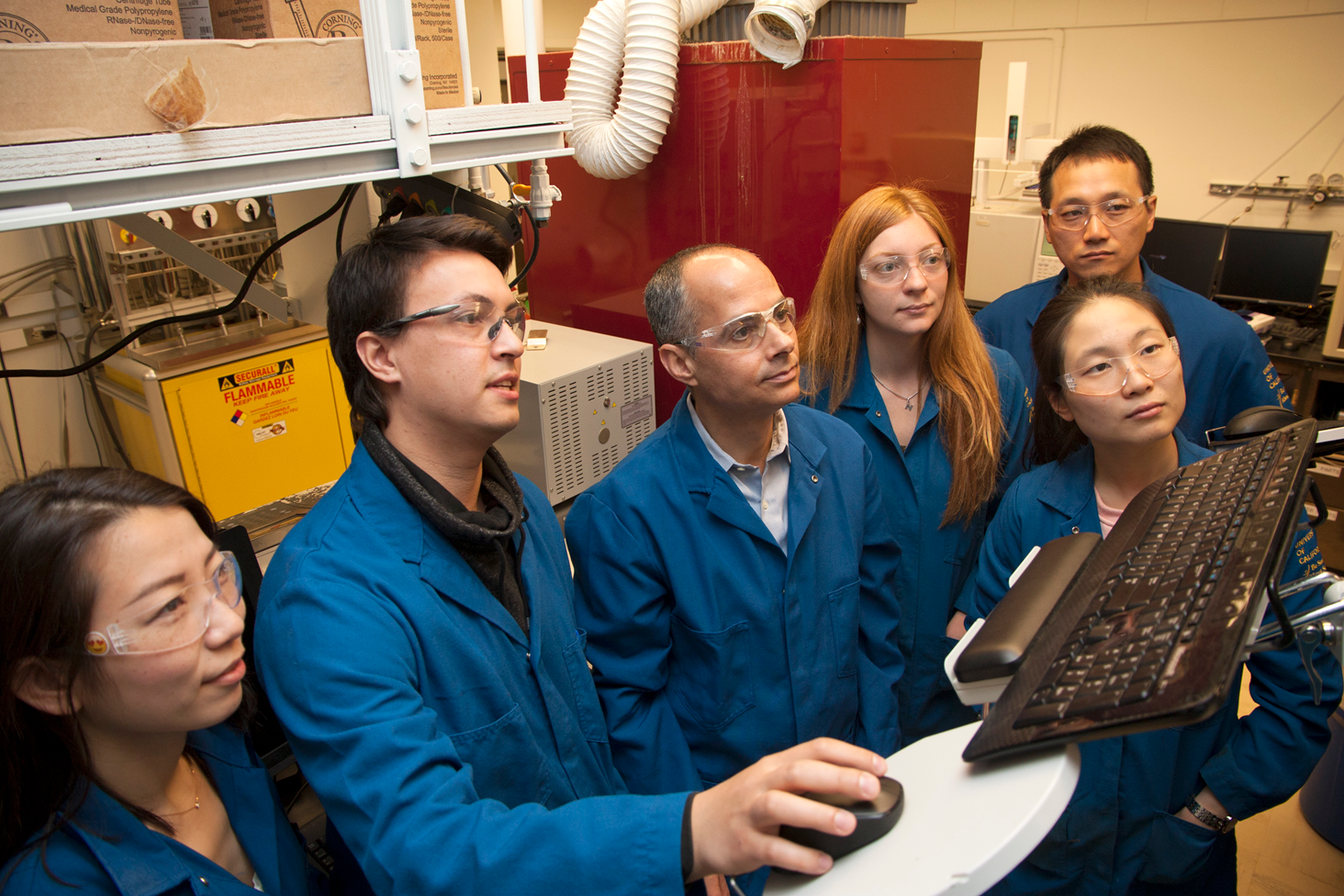

As a professor, Yaghi has also left a mark on many students, researchers and colleagues from different countries.

“The first day I arrived at his laboratory he gave me the keys to his office so I could use it freely and he went to the students’ office. He is an incredible person,” chemist Daniel Maspoch, professor at the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies (Icrea), tells BBC Mundo.

“I was happy when I found out I had won the Nobel Prize.”

Maspoch had seen Yaghi at conferences, but it was in 2019, when he invited him to Barcelona to give a talk, that he was able to get to know him better.

The link was consolidated in 2024, when Maspoch spent time in Yaghi’s laboratory.

“I was able to spend about three months with him and his group. It was an unforgettable experience. He is a very transparent person, he helps everyone, he is a great mentor, a great inspirer, especially for young scientists.”

“When you talk to him, you realize that he really makes you think far beyond the science you do, he goes a step further.

“The degree of reflection it has takes you to moments when you feel that it is worth dedicating yourself to science. Seeing it in action is beautiful.”

“At the same level”

Professor Rodríguez has not only done work with Yaghi but they are united by a friendship that began about 25 years ago.

First they exchanged letters, then emails. And the Spanish scientist told him that he was interested in the area in which he was working.

Yaghi combined organic chemistry with inorganic chemistry in developing metal-organic structures.

“In the scientific part, he sees things with great depth, he is an innovator, he has made precious materials that are also useful,” explains Rodríguez.

“And on the human side, he is a very close person. You might think that the Nobel Prize winner is a conceited person, he is not.”

Something that Rodríguez finds fascinating is Yaghi’s relationship with his students and how he recognizes their work and contributions.

He says that he does not fall short when it comes to highlighting when it is his pupils who have motivated a discovery.

And, for Yaghi, in the environment of scientific research “the student and the teacher are on the same level.”

In the Tang Prize video, he highlighted the importance of always having open channels for questions and criticism.

“That the student is not afraid to contradict the teacher; when that happens, magic arises, you create magic because now you have two people analyzing a problem without being afraid to say: ‘I don’t know’ or to share their valuable idea.

“You need both for a discovery to occur: the student is there, doing the experiment, making observations, making decisions about which observation to follow.”

“Start wherever you are”

After learning that he had won the Nobel Prize, Yaghi insisted on the importance of science in social development.

“You cannot solve society’s problems without science. You need science, materials and the technology that accompanies it,” he said at the press conference.

Many experts are optimistic about the future of metal-organic structures to address several of the challenges we face as a society.

For example, to combat climate change, to capture carbon dioxide and water in places where it is very difficult to access, in the development of clean energy, in the field of biomedicine.

“These materials are one of the most precious, most important platforms of modern chemistry,” says Maspoch.

“Metallorganic frameworks have enormous potential, offering previously unthinkable opportunities to create tailored materials with new functions,” said Heiner Linke, chair of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry.

Yaghi won the Tang Prize “for his extraordinary contributions to sustainable development with his pioneering metal-organic and other ultraporous structures that can be adapted for carbon capture, hydrogen and methane storage, as well as water harvesting from desert air.”

In his speech, at the event in which he was presented with that award, the chemist once again evoked his journey.

“As I reflect on my journey, I remind myself that life rarely offers you the perfect conditions. We often find ourselves waiting for the right time, the right resources, or the right circumstances to start pursuing our dreams.

“But if there is one thing my life has taught me, it is that waiting for ideal conditions can often mean an eternal wait.

“The key is to start wherever you are with whatever you have and trust that with solid thinking the journey will take its own shape as you move forward.”

click here to read more stories from BBC News Mundo.

Subscribe here to our new newsletter to receive a selection of our best content of the week every Friday.

You can also follow us on YouTube, instagram, TikTok, x, Facebook and in our whatsapp channel.

And remember that you can receive notifications in our app. Download the latest version and activate them.